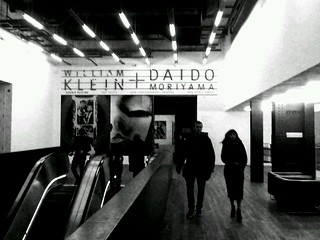

This was the primary reason for the trip to London that saw me take in Light from the Middle East and Seduced by Art (and in deference to my wife Hollywood Costumes at the V&A and Billy Elliott). And I still don’t really know what to say about it. I came for Moriyama, so Klein was an added bonus, and as his exhibition was first in the layout I’ll start there.

I’ll be honest - my mind ended up swimming a bit from the sheer quantity of work on display so some of these recollection may be a bit vague. My handwritten note as I entered the first room says everything about my initial reaction: “It’s huge! Really Huge” – and it was. The opening room, and the entrance wall contained montages of some of his more famous prints – some produced very large indeed – think 8-10 feet high. Coming from a country that doesn’t have a gun culture I’ve always found the ‘kid with the gun to his head’ a bit shocking, even though I know it’s a toy, but blown up bigger than life-size, and coupled with a number of other shots on a similar theme that shock is really driven home.

On the opposite wall are montages of smaller images, some of which were familiar – some less so – and this theme was repeated in the next room - banks of images in his familiar, in your face style. A couple of things jump out here – this was a man who was comfortable in a city, who thrived in a city and just wanted to capture its spirit – and in the process he shows how much cities depend on kids for their atmosphere – a point which struck me again and again after the exhibition. What would the underground be like without the groups of teenagers? The side streets without kids playing? We’ll probably know in 20 years, because the other thing that struck me was that you’d be vigorously duffed up by someone if you took as many photos of kids in a modern British city – which means our photographic legacy risks being childless.

When you see these photos all pulled together like this it really emphasises why it doesn’t matter that the horizons are wonky, the photos are sometimes blurred and the composition is not classical. It’s about vitality, verve and the sheer joy of taking photos.

Improbably I don’t recall seeing the ”models on the zebra crossing” before – but what a great idea – which he seems to have partially replicated in a film showing further on in the exhibition with a Christ like figure standing on the street corner in what I assume to be New York, and unlike the models (if the notes are to be believed) being soundly ignored by all the passers-by. Unfortunately I didn’t get a name for the film – but I suspect it may be The Messiah as it was fairly closely followed by a police choir singing part of The Messiah.

The next room was dedicated to his city portraits New York, Moscow, Rome and Tokyo. Again his love of the vitality of cities comes through – although I had to conclude that actually cities are more similar than they are different. A particularly impactful section was the Japanese action painter who as the notes accurately say, looked like he was splattering blood across a huge piece of paper by punching it until his knuckles were raw. It was only close inspection that revealed it was paint. Unsurprisingly Klein reveals in the notes and the accompanying interview clips that he couldn’t find a publisher for his New York book – my gut reaction is it was far too vivid and real, and had too many home truths, for the times.

Rooms 4 and 5 I found a bit less interesting – one was full of wooden panel featuring some of his early abstracts and another largely given over to some abstract photograms – although the Holland=Mondrian 1954 series was a playful take on Mondrian’s abstracts using the lines of barn walls and windows to replicate the grids of the artist.

Moving on we were treated to excerpts from some of Klein’s movies – Muhammed Ali meeting the Beatles was a wonderful period piece and the craziness of Mr Freedom makes even the Simpsons look sane. Finally as far as Klein goes there was a room with some of his contact sheets blown up very large and painted on. I’d like to pretend that I understood the purpose of this activity – but I’m not sure i do. I can see it as a fusion of his early abstractions with his photographic works, and looking at the notes it was clearly something of a personal expression of joy and freedom for Klein. It also moves photographs out of the realm of being something simply representational and into an object – an idea that one or two of the artists in Light from the Middle East explored, but that only feels like part of it.

There was sufficient work on show in the Klein section for a whole separate exhibition – but my poor saturated brain now had to cope with Moriyama.

“My approach is very simple – there is no artistry. I just shoot freely.” says Moriyama – and if you were to take individual images from the huge body of work on display you might be tempted to agree, but taken as a whole there is clearly something going on which makes you question what he means by artistry. Does he mean aesthetics? I tempted to say not, because he comes over in is writing and interviews that I’ve found on the web as very well able to express himself, but that just leaves me wondering – which may well be the point.

Moriyama’s strong point is photo books and so most of the images in the 6 rooms were presented as montages or sequences, and seen like this they begin to make some kind of wild sense. Hunter 1972 is a case in point – billed as a view of Japan through a car window. I can see, doing a lot of driving, how that works. Snatches of people here, an overhead light there, lingering in the memory in an unformed mash-up of all the images you’ve ever seen through your windscreen. As Simon Baker says in one of the essays in the Moriyama catalogue (for some reason the artists didn’t want to share a catalogue) “In these works the photographic image loses its indexical grip on the journey, giving itself over to a delirious revelling in the strangeness of automotive visions: speed, motion, night-time headlights, rain swept windscreens and the world receding in the rear-view mirror.”

Moriyama’s cities are different from Klein’s. They have fewer people to start with – and sometimes the people aren't real, they’re mannequins in shop windows, or wall posters. Sometimes it’s clear which, sometimes it isn’t. Klein's patch is the busy daytime street – Moriyami’s is the night-time - when the underbelly is even more exposed. You could imagine the pictures displayed as a slide show with the words of Pink Floyd playing in the background – “Moving in silently, down wind and out of sight, you’ve got to strike when the moment is right, without thinking.” Where he does shoot people, they seem to be as individuals or in pairs – with the exception of Accident 10: Sombre Sunday – which is a claustrophobic series of images of a packed beach done in his characteristic near abstract high contrast, so that it reminds me of his supermarket shelves in Provoke.

One down side of this vast range of subject matter and treatments is that it’s very difficult to analyse – even remember – individual images – and those that I do remember are often a result of having see them before so I’ve been looking out for them. But what does stick in your mind is the simply bizarre – the close ups of lips (hoarding or reality?), the woman with the piercings, the headless body (or was it?) the car accidents and shipwreck.

I was interested to see Farewell Photography and after (yet again) having to admit to myself that I didn’t really understand what the collection of print's from water damaged, scratched and torn negatives was really about it was quite a relief to discover that Moriyama has described the book as “pure sensations without meaning”.

And yet – amid all this chaos, in Room 4 we find that Moriyama can be studied and reflective as well. Light and Shadow 1981 and How to Create A Beautiful Picture 1987 are extended studies in light and form, finding beauty in the mundane by the simple expedients of contrasting light and dark and composition. “No artistry”? I’m still not convinced. And further on, in room 5, we find a slide show of photos taken during his time in Hokkaido, the run down surroundings capturing a melancholy feel as he was apparently going through a personal crisis at the time. Nearby was one of my favourites. Over a period of several days he photographed the entire inside of his studio with a polaroid camera, and re-assembled it as a 3-D room-sized mosaic on all four walls to provide an image of his studio which captures time as well as physicality. The change in pace between these later rooms and the earlier stuff was very marked, and left a significant impression on me.

But, lest we think that the hunter is going soft, we finish off with “Stray Dog” – his signature photograph – printed in several different ways and at various sizes. There is undoubtedly something about the dog that makes it unforgettable. Is it dangerous? Is it slavering? Or is it simply beaten down by the city? I guess we’ll never know – but it is clear that Moriyama has been reasonably comfortable to be identified with it to the point where he called his autobiography “Memories of a Dog”.

And so it ends. I could never have guessed from the few individual shots I’ve seen in books that Moriyama’s real interest appears to be memory and time – perhaps that’s what has attracted me to his work and I shall look forward to the next opportunity to see it. Klein was fascinating – but for me at least Moriyama was enthralling and stole the show.

“I think that the most important thing that photography can do is to relate both the photographer and the viewer’s memories.” Daido Moriyama

No comments:

Post a Comment